Content Warning: This page and the linked posts contain references to hunting, agricultural, and research practices of killing birds. This page contains a photo of a Mallard hunter with his kills. If you choose not to read on, I respect and admire your choice.

Starting in 2024, I’ve been on a journey with Mallards.

Journey. Perseveration. Obsession. All are accurate.

What began as an exploration of flight muscle physiology, in nesting Mallard hens, grew into a ramble through archival Mallard literatures. There I found a gateway into a massive, and massively complex, system of historical Mallard texts. Mallard subtexts, really. A vast labyrinth of Mallard literature, composed around a vastly valuable resource.

Mapping the Mallard Mine

Conservation and wildlife literatures are familiar territory for me, but the Mallard context was new. And, it turns out, North American Mallard context is deeply entwined with North American history. With US history. With further back history, too. Because Mallards are the domestic species—the “stock duck” for many of our familiar barnyard flocks. And Mallards are the game species, as far as North American ducks are concerned.

The particular thread I’ve been following, through the Mallard Mine, is the historical and (still emerging) regulatory landscapes of Mallard hunting. Because Mallard history is hunting history, and hunting history is regulatory history, and regulatory history is the politics and law around resource ownership. Around commerce. And commerce, in our capitalist society, is everything.

It’s ridiculous to claim that Mallards are at the center of everything. But Mallards are in the mix, there at the center. The species has been one of North America’s most abundant, and most abundantly harvested, resources. A renewable resource, for certain, but not infinitely renewable.

The Title Deed (or, who owns the Mallards?)

As a continental resource, North American Mallards belong both everywhere and nowhere in particular—from Canada to Mexico and everywhere in between.

I don’t have access to (or the wisdom to interpret) pre-European power structures around resource ownership, but it’s reasonable to assume that, in some distant North American past, Mallards belonged only to themselves and their watery habitats.

After the European invasions, pre-revolution colonies followed European traditions in which resources belonged to the aristocracy. But many pre-revolution colonists, and all post-revolution colonies, avowed democratic ownership of resources. For them, The People (the invading European people) owned the Mallards. Then, in the late 1800s, individual state governments claimed ownership of all wildlife within state borders, holding the resources “in trust” for The People. Still later, for a few short years in the early 1900s, the US federal government wrested control of birds, both game and non-game birds, from the state governments. (If you read that and thought, “wow, was that in the constitution?”, the answer is no. That most definitely was not in the constitution.)

Now, North American Mallards belong to a treaty-bound group of nations. (Except for the Mallards that belong to hunting clubs, which exception waits heavily at the end of my particular thread-path through the Mallard mine.)

If all of this sounds a bit familiar, that’s because the story of Mallard ownership parallels many of the more familiar chapters of US history.

The Contracts (or, I found my purpose in the fine print)

The ownership trail, itself, was a series of statutory grabs. Of (sometimes) hostile takeovers. And each takeover resulted in new apportionments of harvest rights. New bureaucratic fine print.

Very early in my Mallard journey, I found a single statement in a single report from a single committee. A statement that I initially set aside as too complex for my limited understanding and too controversial for my limited intent.

I set it aside, and yet I brooded. Eventually my brooding hatched and demanded to be nurtured.

Now my Mallard journey has a policy-argument purpose. And the policy argument purpose is what drives me to keep reading and keep writing.

Policy isn’t my lane, so my purpose needs beginner-level groundwork. Both historical groundwork, because my original limited intent for this blog is an obstacle, and personal groundwork, because my limited understanding is a more problematic obstacle.

In order to place my policy argument in proper context, I need to understand the history of North American Mallard hunting regulations and conservation efforts. And in order to condense my policy argument into clear terms with clear purpose, I need to expand my understanding of topics beyond my current educational and experiential horizon.

And since I’m doing the work, I might as well share the work.

That’s the long version of the story behind this Mallard blog series.

The short version is that this blog series is an exercise learned in elementary school…show your work.

This is my work. It’s made of time and words and photos and obsession. Of Mallard history, US history, and personal history.

Whether you’re here for the photos, for the story, or for the history, I’m happy you’re here. Welcome to my Mallard obsession perseveration journey.

The Mallard Journey (so far)

Part I: The Flight Muscles

In which a backyard Mallard encounter sets off a lasting obsession with Mallards, in general, and backyard Mallards, in particular. My gateway question was What happens to a Mallard hen’s flight muscles when she stops flying? Because Mallard hens pretty much stop flying, altogether, during their month on the nest and then two months shepherding flightless ducklings. At least, their flight time decreases drastically. Do their muscles shrink, during this time of disuse?

Here’s the Mallard hen who started it all. Doesn’t she look like she’s ready to start something?

Part II

In which I got philosophical. About knowledge vs. knowing. About science’s failure of transparency regarding colonialism and capitalism. About the cost of science, sometimes obscured by euphemisms within the literature and sometimes hidden in the reference section. And in which I found a set of articles that opened a door into flight muscle literature, where my original question still awaits an answer. Here’s that hen again, oblivious to questions about flight muscles, fully invested in caring for her hatchlings.

Part III: Annual Changes in Flight Muscles

In which I cherry picked a non-answer from flight muscle physiology literature about molting. Barnacle Geese, Great Crested Grebes, and Red Knots. (Oh my.) There were also Mallards in molt. And a grand total of 11 wild Mallard hens captured and recaptured (and, some of them, recaptured yet again) in North Dakota, in 1981, during nest season. After those 11 hens, all traces of a potential answer to my original question vanished. But, as I had already settled in for a long adventure in the Mallard literature, I kept reading. Here’s the hen from 2024, looking as if she knew the answer I was searching for, all along (she undoubtedly did), but had no intention of sharing.

Part IV: Positioning My Perspective(s)

In which I rummaged through personal history to sort out my past and present feelings about livestock—about living stock. About animal protein on the table. About “eating the animals and dissociating”. And about the generational hunting habits that helped shape my perspective on Mallards. Here’s an old family photo, bearing an unfamiliar and not-family name, of a hunter with his Mallard harvest.

Part V: Hunting by the Numbers

In which the tangents take over. An introduction to the Mallard Mine. Sport hunting. The dollars (so many zeros) spent on waterfowl hunting in the US. The Mallard population census. Ranges and seasons for Mallard breeding, migration, and overwintering. Harvest numbers, historical and current. And an introduction to the first documented Mallard population crash, circa 1920. Here’s a photo of one of the Mallard hens who brought ducklings to the yard, and to the dragonfly pond, in the spring of 2025.

Part VI: States claim the game

In which I started by addressing the very large and not invisible at all elephant in the room: my lack of a discourse through which to find, engage with, and/or interpret pre-colonial North American history. As one of Europe’s descendants, I’m only equipped to tell one part of the Mallard story, “…the part written by and for Europe’s descendants.” (I very much hope that, some day, science literature will start letting descendants of North America’s original nations tell the pre-invasion stories of North America’s wildlife and habitats.)

The rest of this installment dealt with distinctions between sport hunters and market hunters, early America’s meat-and-feathers market (and the massive strain this market placed on wildlife resources), and the passenger pigeon extinction event. The final sections introduced the first set of statutory grabs, when state legislatures began claiming ownership over game resources within their borders, and a few snippets of early case-law: Peables v. Hannaford (Maine, 1841), Missouri v. Randolph (Missouri, 1876), and Kansas v. Saunders (Kansas, 1877).

Note: Part VI expanded on an earlier photo archive experiment, weaving family photos into the text. One branch of our family tree was photo-wealthy, and some of their collection passed into my generation. Here’s a photo, c. 1900, of an unnamed pair of women decked out in feathers and fur.

Part VII: Game informants, game police, and the end of the game market

In which states (and pre-revolution colonies) experiment with ways to fund game legislation. Many resorted to offering informant payouts, as part of their policing efforts. So very many opportunities for corruption, including samples of legislation from Virginia, California, and Maryland. Asides about Robin Hood tropes, debtors’ prisons, and unpacking resonances. Then Magner v. The People (1881), in which the Illinois Supreme Court ruled against a game merchant convicted of close-season quail possession.

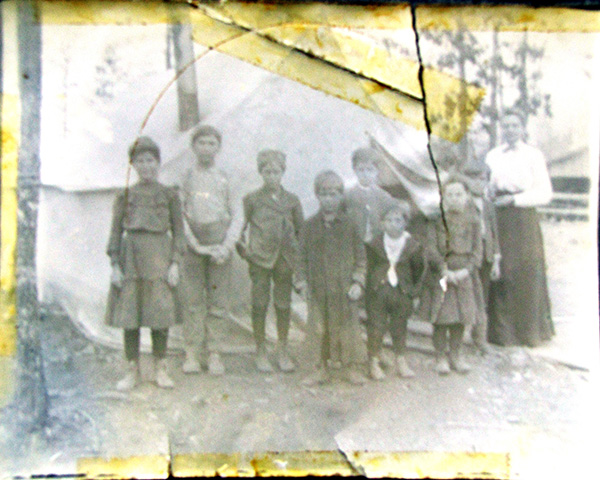

Also, I found a way to include one of my favorite photos from the family archive—an unknown group of children posing with a chaperone-figure in front of what I imagine to be a tent-style schoolhouse.