Content warning: This blog post contains references to the hunting, agriculture, and research practices of killing birds. If you choose not to read on, I respect and admire your choice.

Part of my purpose in writing this Mallard series is to highlight the price that has been paid (and continues to be paid) for the knowledge we have about Mallards and other birds. I might have constructed these posts, as a younger writer, without acknowledging the deaths behind the data. But as I’ve aged, I’ve grown more aware of the cost of knowledge.

What I mean by “knowledge”

It’s one thing, for me, to observe our yard and its visitors. To slip away from human concerns and simply watch. To sate myself with wonder. These hours shift my perspective. They build new connections between old memories. I sometimes emerge with splintered metaphors to sand and patch and paint. Sometimes with fine-grained phrases that liven up a drab idea. On the rarest and best days, I emerge with blueprints for new knowledge.

Observation and wonder are one thing. But knowledge is an entirely different state.

Separate and distinct from the metaphysical implications of knowing, my definition of knowledge is an inventory of education and experience. The nouns of my past and the context in which I encountered them, indexed by subject and era. A cross-referenced heap of biology, shuffled around the edges with chemistry. A shelf of style guides and writing advice. A few notebooks of math, physics, and cosmology. A faded box of recipes, crochet patterns, and needlework hints. Stacks of genre reading. Great aisles of emptiness where business, economics, and law failed to catch my interest.

I was recently asked to list my areas of expertise. I wanted to respond that I have none. I am a worksite traced with utility locator flags, not a finished library. I might claim my main parlor, biology, but even there the framework is incomplete. And, to align the metaphor with my theme, construction materials are expensive.

For many long decades I failed to appreciate the cost of knowledge, with its scaffolds of data. In this post, I’ve chosen to pull back the curtain I so blithely ignored as a young science student. Much of what I find behind that curtain forces me to stock those great empty aisles of business, economics, and law. Because the dimly-lit ledger of science history, written mostly by rich old white men, seldom accounts for cost. But every so often, jotted in the margins or tucked between the pages, the writers left remnants of their invoices.

The capitalism behind the curtain

During my brief foray in the humanities silo, I chafed over intense criticisms of science and science writing. But I couldn’t deny the foundational weakness. Science motored along for centuries, impervious to criticism, fueled by colonialism and capitalism. For the most part, it still does.

What would it look like, if science and science writing discarded the curtain and directly acknowledged the capitalism? The colonialism? Not just here and there, but in every published report? If the ledger was complete and brightly lit?

I don’t expect a humanities-approved (and strengthened) science literature would look like anything I can imagine. I am neither scientist nor science writer. What’s more, my little graduate certificate in professional writing is not a stamp of humanities approval. So I can’t answer the questions that followed me home from the humanities silo.

But I am an avid science consumer. As such, the word cost is not chosen lightly. Whenever I look behind the curtain of knowledge, no matter the era or discipline, I find the busy (and visible) hands of capitalism.

As ubiquitous as hunger, questions are free for anyone who has the energy and time to ask them. But answers? Answers are capital. They are expensive. And, weighed in the hands of capitalism, answers are expected to reap a profit.

What happens when answers are not synonymous with capital gain? When hunger lingers or multiplies because the investment outweighs the return? In very short order, the hands of capitalism divert resources and time toward less costly questions and more profitable answers. Or, at least, toward questions perceived to be less costly and answers anticipated to be more profitable. The question I should have been asking for years, the question I am asking now, is this: Whose perceptions and anticipations control the resources?

Some practicalities about Mallards and other waterfowl

Historically, Mallards had value (and have value, still) because they were and are hunted and farmed. When it comes to funding research, and to collecting data for research, hunted and farmed species are valuable, easy resources. “Valuable” in the capitalist sense of being actual capital, but also in the academic sense of data. “Easy” because these species live and die in larger, more accessible numbers than similar species that are neither hunted nor farmed.

Hunted waterfowl (and other game birds) live and die in their large numbers within easy reach of researchers. I can’t write a path around the pragmatism of this system, but I am increasingly uncomfortable with such pragmatism.

As capital, a Mallard’s value is tethered to its food and sport potential. Driven by this food and sport value, research funding adds further value to a Mallard. Each bird is data. Whether hunted, farmed, or recorded into a set of measurements, a Mallard’s value peaks with its death. (Perhaps this is true of every individual, of every species, but I’ll leave that notion for a later post.)

What of this spring’s next-yard hen, with her downy brood? When I perceive them as more than units of capital, when I anticipate their ongoing existence as more than a value that peaks when they die, my ability (and desire) to control them as resources wanes. For me, this feels like a good and useful adjustment of my perceived and anticipated place in the world.

The older I get, the less comfortable I am with capitalism and its pragmatisms. Far from being an agriculture, research, or policy pragmatist, I want the next-door hen and her offspring to have an embodied value separate from their muscle mass and plumage. I want empathy to count. My still and quiet moments in the yard. The silly antics of ducklings in a dragonfly pond. The charm of infant proportions and curious hungers. I want to measure value as a sense of shared life, a shared world, and shared safety or peril.

Aside: the literature’s euphemisms for “kill”

According to Google’s default dictionary, the word euphemism is derived from the Greek roots eu-, meaning “well”, and -phēmē, meaning “speaking”. I was taught, somewhere in my education, to translate euphemism as good word. But in my more recent years I have come to view euphemisms as veiled words. Intentional deflections. Syntactical high ground for writers (and researchers?) who wish to describe expanses of quicksand without getting mired. I sympathize with the impulse to build polite nomenclatures. To write around shock words and trauma words. But we’re all in the quicksand, no matter what we write.

(Remember the opening content warning? I do understand the need, the profound and pressing need, to protect victims of shock and trauma from experiencing further shock and trauma. This is why I embrace the practice of content warnings. The remainder of this blog post contains frequent references to the research, agriculture, and hunting practices of killing birds. If you choose not to read on, I respect and admire your choice.)

Policy, agriculture, and hunting literatures shy from the words kill and slaughter. “Kill” is rather imprecise, I suppose, for research literature. And “slaughter” is a bloody word, even with its Merriam-Webster finesse—“the butchering of livestock for meat”. In that sense, I acknowledge that “slaughter” is imprecise, as well. The birds (including Mallards) that populate policy, agriculture, and hunting literatures are resources. They are capital and data, not meat. Does it matter how we describe their deaths? (Yes! Of course it does.)

In the literatures, birds (including Mallards) are hunted, shot, collected, harvested, culled, sacrificed, and euthanized. Dead birds are examined, necropsied, and sampled. Wings are placed in the mail.

For this post and its subsequent parts (I’m not certain how many parts there will be), I’m choosing the word slaughter. Because I added up the numbers behind the data. The research numbers in the tiny subset of articles referenced here run into the thousands. The hunting numbers, hundreds of thousands per year. I feel the word slaughter fits.

The rest of my multi-part Mallard post draws heavily from work done by and for the research, agriculture, and hunting industries. Birds died for these questions and answers. For better or for worse, this is the world we have shaped for Mallards and their avian kin.

The research numbers

The following section, which deals with variations in the relative sizes of flight muscles, leans heavily on an article by D. C. Deeming, PhD.: “Allometry of the pectoral flight muscles in birds: Flight style is related to variability in the mass of the supracoracoideus muscle.” Deeming’s article pulled data from three primary sources: two tracts (1961 and 1962) from the Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections and a 2016 survey out of Romania.

- Greenewalt, C. H. (1962). Dimensional relationships for flying animals. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 144(2).

- Greenewalt collated pectoral muscle weights from a 1922 French publication: Magnan, A. (1922). Les caractéristiques des oiseaux suivant le mode de vol. Annales des sciences naturelles, Series 10, Volume 5, 125-334. (Yes, that is the same Antoine Magnan responsible for the urban legend that bees should be mathematically incapable of flight.) Magnan’s work used captive birds and, as Greenewalt cited, “…those which appear to be in bad health were discarded” (Greenewalt, 40). Some 228 birds, representing about 223 species, were slaughtered for this data. (I’m hedging my numbers because counting=math=possibility of error.)

- Hartman, Frank A. (1961). Locomotor mechanisms of birds. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 143(1).

- Hartman’s tract drew from more ambitious work that took place in Florida, Maine, Ohio, and Panama. Birds were “collected” (or, even more euphemistically, “obtained”) from January to March, mostly before 11 AM (p. 3). The method of collection isn’t specified, nor the method of slaughter, though the authors specify that birds and their dissected muscles were weighed in “fresh condition” (p. 2). The pages and pages of data (pp. 38-91) represent more than 360 species. Individual numbers range from 1 (i.e., a solitary Bicolored Hawk of unknown sex and a single male Ruddy-capped Nightingale Thrush) to 50 or more (i.e., 55 House Sparrows, 51 White-breasted Nuthatches, 52 Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds, 50 Smooth-billed Anis, and 103 Brown Pelicans). In total, more than 6000 birds. (Again, hedging because math.)

- Vágási, C. I., Pap, P. L., Vincze, O., Osváth, G., Erritzøe, J., & Møller, A. P. (2016). Morphological adaptations to migration in birds. Evolutionary Biology 43, 48-59.

- Vágási et al. captured and banded live birds in Romania, but also “[c]arcasses from natural deaths (e.g. road kill, building collision, electrocution, starvation) were collected in Romania and Denmark for taxidermy” (p. 50). The authors clarify, “Numerous bird specimens were brought frozen to JE, more than 95% of them being found dead and the remaining were shot by hunters” (p. 51). The dataset, here, includes some 115 species. Sample sizes ranged from single individuals (i.e., one Grey Wagtail , one Peregrine Falcon, and one Whinchat) to more than 100 (i.e., 824 House Sparrows, 228 Eurasian Blackbirds, and 193 Eurasian Sparrowhawks). In total, more than 3800 birds. (This article models a practical and effective approach to science without fresh slaughter, primarily sourcing data from carcasses submitted for the study. Granted, “natural deaths” from road kill, building collision, and electrocution are hardly “natural”, but I appreciate the distinction between carcass repurposing and the slaughter of otherwise healthy birds for research purposes.)

So Deeming gleaned data from more than 10,000 birds, without listing a single slaughter in the Materials and Methods section. This is both efficient science and inefficient communication. The actual numbers were curtained off, in at least one case, two sources deep and a century back. I applaud the reuse of data, but I resent the legwork required to find the birds within the data.

I expect that most of The Journal of Zoology‘s readers feel no need to find the birds. After all, the article’s intended audiences hold greater and deeper knowledge of birds, wings, and flight than I bring to the moment. The author and intended audiences would likely characterize my stroll down the numbers rabbit-hole as a tangent prompted by unrealistic purposes and fueled by OCD. But, was it?

What is the capital, here? Or rather, which capital is more valuable? The answers and knowledge, so satisfactory to my passing curiosity? The data and findings, so neatly packaged for future reference? Or the birds themselves, so fleetingly alive?

Ask a different me, in a different era, and my response to these questions would change. But, for now, my heart yearns toward the birds so fitted for flight as to seem almost magical, winging through yards and migrating over landscapes and dabbling with their downy chicks in dragonfly ponds.

Variation in the relative masses/sizes of flight muscles

(For specifics of flight muscle anatomy, see Part I of this post. In short, two muscles power bird flight: the large pectoralis muscle, which powers a wing’s downstroke, and the smaller supracoracoideus muscle, which powers a wing’s upstroke. Both muscles stretch across birds’ chests, from wing to sternum. If you eat poultry, these flight muscles are the breast meat.)

An average bird with average flying habits pushes down against air with its downstroke muscle, wing extended and feathers angled to maximize (or to finesse) the lift. How much force is needed depends on the birds’ weight and acceleration. Is it a heavy-bodied duck or a sleek-framed crow? At a minimum, the downstroke muscle is massive enough to lift the bird’s weight against gravity and accelerate according to the bird’s habits. Imagine the initial heaves of a Mallard taking flight. The lazy hop-launch of a crow. Which bird has bulkier downstroke muscles?

Back to the average bird with average flying habits, downstroke accomplished. Now it tucks and rotates its wings, to minimize air resistance for the upstroke.

Push (PUSH) down. Tuck. Pull (pull) up. Flap. Flap.

Large downstroke muscle, for the heavy work of lifting body weight against gravity. Much smaller upstroke muscle, lifting only the weight and feather-drag of tucked and rotated wings against air. Whether Mallard or crow, the upstroke muscle does less work. (Read on for exceptions, because there are always exceptions.)

In average birds with average wings, downstroke muscles are between 8 and 13 times larger than upstroke muscles (Deeming, “Discussion”, para. 1). So much pushing, so little pulling.

But what about not-average birds? What about birds with exceptional flight habits? What about flightless birds?

Some birds need to pull (PULL) as they raise their wings. They need a mightier upstroke muscle. Penguins, auks, and many other diving birds use their wings under water. No matter how much they tuck and rotate, water isn’t air. There’s more drag. These birds’ upstroke muscles are large, both in proportion to their downstroke muscles and in proportion to their body sizes. Their downstroke muscles are still the largest flight muscle, but only about 1 to 3 times larger than the upsized upstroke muscle. No more of those 8 and 13 numbers (Deeming, “Discussion”, para. 2).

Hummingbirds, which actually rotate and invert their wings during the upstroke, generate lift in both phases of the flap: push (PUSH) and pull (PULL). Surprisingly, to me, pigeons also generate lift in the upstroke, via a trick of the wing tip to change their wing shape. Both hummingbirds and pigeons measure in the same range as diving birds that swim with their wings; their downstroke muscles are only 1 to 3 times larger than their upstroke muscles (Deeming, “Discussion”, para. 2 & para. 5).

More special conditions occur for flightless birds, such as Rheas, and for owls and hawks. More special distributions of muscle. The Deeming article is packed with details.

I didn’t mean to write this much. But I’m fascinated. And I have OCD. It’s a dangerous combination, where tangents are concerned. But in the next part of this post, I’ll move on to flight muscle changes during a bird’s life cycle, as there is plenty of evidence regarding changes in flight muscle mass during molt.

Publication Announcement!

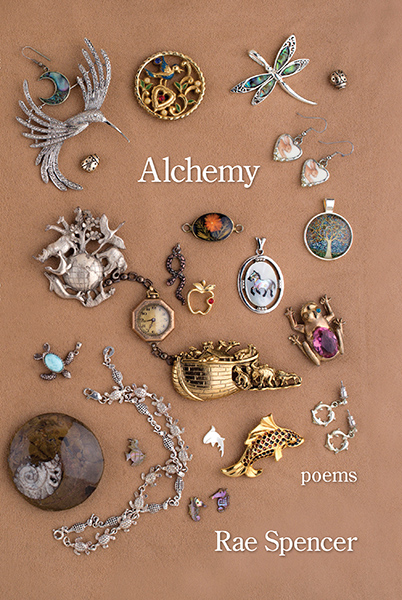

If you’re still here, I very much appreciate your time and attention. And, while I do feel a pang of irony as I promote my own writing while complaining about capitalism, my second poetry collection is now available!

Alchemy is a different kind of collection than my previous Watershed. The poems in Alchemy are arranged in five sections after the style of academic articles: Introduction, Methodologies, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. The poems celebrate my fascination with science and the history of science, but also express my yearning for the kind of metaphysical knowing I referenced earlier in this post. I hope readers feel their own celebrations and yearnings, as they read. Alchemy is available in paperback ($20) from Kelsay Books and in paperback ($20) or Kindle ebook ($9.99) from Amazon.

References

Deeming, D. C. (2023). Allometry of the pectoral flight muscles in birds: Flight style is related to variability in the mass of the supracoracoideus muscle. Journal of Zoology 319(4), 264-273. https://doi.org/10.1111/jzo.13043

Greenewalt, C. H. (1962). Dimensional relationships for flying animals. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections Vol 144(2).

Hartman, F. A. (1961). Locomotor mechanisms of birds. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections Vol 143(1).

Vágási, C. I., Pap, P. L., Vincze, O., Osváth, G., Erritzøe, J., & Møller, A. P. (2016). Morphological adaptations to migration in birds. Evolutionary Biology 43, 48-59. https://doi.1007/s11692-015-9349-0