Content warning

This multi-part blog post contains references to the hunting, agriculture, and research practices of killing birds. This particular installment contains references to hunting other prey and killing chickens from a backyard flock. If you decide not to read on, I respect and admire your choice.

Livestock are living stock. And sometimes pets.

Until they are not.

Growing up in rural Tennessee, I had daily exposure to food chain realities. Our freezers (we had two) were stocked with meat from assorted livestock we raised. Livestock we loved. Chickens and cows, during my memory years, with vague early memories of pigs.

Our chickens and cows and pigs had individual names and individual personalities. We raised them and cared for them and loved them. But food chain reality means that livestock exists to be eaten. No matter how cherished. No matter how tame.

Off to slaughter

Our cows and pigs were slaughtered and processed by local-ish butchers, but Mother slaughtered our chickens with a hatchet. Then she cleaned and portioned their carcasses while I collected and bagged bloody feathers.

In reviewing family archives for this post, I was struck by how similar the above scene is to a photo from the early 1900s, found in our maternal grandmother’s album. There was clearly something generational going on at our table.

Wildlife can also be living stock, to a hunter

Small and sundry prey

In addition to eating chicken, beef, and pork raised on our property, we sometimes ate squirrels and rabbits shot by my father and brothers. It’s possible that our beagles sometimes helped on these hunts. (It’s more likely that our beagles hindered these hunts.)

I helped skin and clean the squirrels and rabbits, and I remember being fascinated by their soft fur. I also remember Mother muttering and tsking while she cooked squirrel and rabbit meals. She breaded and fried the meat, and served barely edible, extremely tough portions with open disdain.

I developed a lasting case of meat snobbery, rooted in Mother’s disdain. Squirrels and rabbits were in the lowest edibility tier. Nothing lower was served. No frog legs. No snake, turtle, or alligator meat. No opossums.

Something generational was going on at our table there, too, but in the opposite sense of backyard flocks. Mother preserved her family’s tradition of raising chickens for slaughter, but put a permanent end to the family tradition of opossum hunting. (Scroll quickly if you don’t care to see a sepia-toned group of early 1900s ancestors showing off a bunch of dead, dying, or faking-death opossums, along with the dogs that facilitated the hunt.)

That’s my grandmother, second from the left, one hand behind her back and the other hand dangling an opossum for the camera. This particular hunt (it wasn’t the only time the family hunted and ate opossums) was special because one of the cousins (Sarah Harrison, standing on the far left) had come to visit.

I should add that Mother’s disdain was not coherently taxonomic. Reptiles, amphibians, and insects were off the menu, but so were ducks, geese, and goats. Which meant some of our livestock were exempt from slaughter. What’s more, “dairy” came from cows and cows exclusively. There’s no logic here, only family and cultural tradition.

Cue any stand-up comic mocking a southern drawl. For that matter, cue any bully standing in their own tradition, mocking other traditions.

In my late teen and early adult years, my oldest sister’s boyfriend often gifted us venison. I was particularly fond of what I called “Bambi roast” and “Bambi spaghetti”. Bambi, it seems, ranked high in my edible-mammal hierarchy. A bit below pet chickens and cows, but certainly above squirrels and rabbits. Which were at least on the list. Unlike opossums.

Here in my middle years, my childhood memories of skinning squirrels and rabbits seem dreamlike. As if those skinny arms and small hands weren’t my own. After all, any brief stroll through my blog history will find some tender post about squirrel and rabbit nests. I cringe, extra, thinking about any of the yard’s visitors heading into a hunter’s sights, then into a frying pan or stew pot.

But I didn’t always equate animals, my own pets and livestock in particular, with the meat on my table.

Further aside… so many eggs

Gathering the eggs

On mornings when my oldest sister was too tired or busy or sick to tend the chickens, I was roused and sent in her place. I remember egg gathering as sleepy, smelly, spidery work. Early morning work. (I’ve never been an early morning kind of girl.)

Egg gathering meant wrestling the chicken pen latch, which grew tighter each year as the posts and gate warped. Then I had to put down my bucket—to unclip the rusty chicken house latch and heave the rickety door over hills of weeds, dirt, and dung—and usually had two or three hens perched in my hair and on my shoulders by the time I bent to retrieve the bucket. Finally, I would stumble over the plank sill into the warm, dimly lit interior.

(Yes, I always stumbled. My severe astigmatism couldn’t navigate the sudden change from light to dark, and the hens dashed in and out through the door in frenzied delight.)

Our chicken house was closer in size to a closet than a house. I don’t have any chicken pen/chicken house photos to share, but almost any wire pen around almost any vine-covered tin-roof-and-plank outbuilding would be an accurate visual.

Veils of cobweb hung from the low rafters. Snakes, flies, wasps, spiders, and light entered and exited through gaps in the walls and roof. A short row of nest boxes lined one wall. The floor was dirt, feathers, dung, and broken shells. The chicken house smelled strongly of chickens and dust, but also of cat urine (from our army of yard cats) and dog feces (from the adjoining dog pen) and, every so often, of predators.3

Shooing hens from their nests, or reaching beneath those who refused to be shooed, I gathered eggs by touch more than sight. (It’s not as easy as it sounds. Our hens didn’t give up their eggs willingly, especially to the tentative little sister of their usual egg-gatherer. Wing slaps left bruises, and claws and beaks drew blood.)

The warm, sticky, tough-shelled eggs that I gathered didn’t feel like they held nascent chicks and ducklings.

Breaking the eggs

Our father began leaving during my pre-teen years. He sold the cows, let the fences lay where they fell, and stopped shoring up the barn and sheds. After he finished leaving, neglect cascaded into decay. Vines pulled down the chicken house and the gate fell off the pen.

Both pre- and post-chicken house era, egg gathering mistakes were inevitable. In the chaos of the crowded, rickety henhouse, broody laying hens stole eggs from the adjacent nests of setting hens. Predators and predator alarms rolled and bounced eggs between nest boxes. An egg laid by a setter a week or more ago, carefully incubated since, might end up alone in a layer’s nest. An egg laid by a layer last night might end up in a two-weeks-along setter’s nest.

After our flocks were entirely free-roaming, they hid their nests so well that eggs were often days old before being found. Eventually, increasing incidences of “bad eggs”, coupled with decreasing egg demand as siblings moved out, halted all egg collecting.

The term “bad eggs” most obviously referred to rotting or rotten eggs. The kind that burst on their own or floated in water. But “bad eggs” also encompassed fertilized eggs that were mistakenly collected mid-incubation.

When an incomplete carcass, some mid-development stage of a chick or duckling, spilled from an egg I had cracked, I writhed with regret. It happened often enough, in my early years, that I still crack eggs into a separate bowl when cooking.

After our egg-collecting years ended, our increasingly feral flock was left to hatch and raise what young they could in whatever nests they chose.

Growing up in rural Tennessee, eating the animals and dissociating

While my egg-mistake memories are mostly visual, wetly curled bodies in a puddle of albumin, my memories of chicken, squirrel, and rabbit carcasses are sticky with remorse and smell like blood, grease, and guilt left out in the sun.

But expressing regret, remorse, or guilt at the table was forbidden. So was refusing to eat what was served. I don’t remember being told these rules, nor do I remember hearing these rules explained to my siblings. For that matter, I don’t remember learning these rules.

It is this lack of learning, this full memory cache with no record of creation, that warrants using the word “dissociated”. As a girl growing up in rural Tennessee, I dissociated from the eggs and meat on our table.

I coped with my forbidden regret, remorse, and guilt by inventing a private delusion, by defining eggs and meat as a different form of matter than living animals.

Depression on top of dissociation

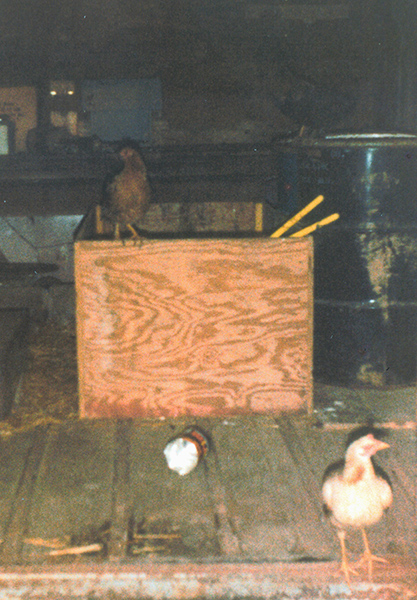

The photo immediately below is more metaphor than image. The worn paint and sagging shingles on our house and concrete-block wellhouse, the decaying barn-remnants to the far right, the unkempt pasture and yard, and the overgrowth marking downed fences. All of these illustrate the state of our dysfunctional household during my teen and young adult years.

The hungry cats and hen on the wellhouse roof, waiting for a meal of table scraps and cheap kibble, are confusion, sorrow, and loneliness. This was the era of boyfriend venison and day-old bread. Of freezers stocked from clearance ads. Of oldest sister tending the garden in the dark of too-early mornings and too-late evenings because she was working three jobs while going to college.

We no longer ate the livestock we raised and loved, but clearance-case chicken and ground beef added a new facet to my dissociation. Grocery eggs and meat were always cold and bloodless, had never been embodied in the yard. And I had learned what it meant to be hungry.

Re-associating, for health reasons

Or, “Thanks for the genes, Dad”

My father died of heart disease at the age of 52. I was mid-teens, and he seemed so old. But he wasn’t old. I am, currently, older than 52.

I don’t feel so old.

I like being me, and I would like to continue being me for some good long number of years past 52.

Perseverating on 52

One of the ways I’ve packaged and carried grief is a fixation on 52nd birthdays. As each of my four older siblings passed 52, I breathed a bit easier. Long before I reached 52, I began researching and planning. Partly because of the grief fixation, but also because my cholesterol levels have been alarming physicians since I was a teen.

Note to father: Next time, maybe try leaving us money, instead.

Statins and exercise are no match for my father’s genes. My last resort for living past 52 was a complete overhaul of my diet. (I should have started there, but I’m a silly human with silly human habits.)

Call it plant based. Call it vegetarian. Call it desperation.

An unexpected side-effect of my diet overhaul has been re-associating with animal protein. My health ambitions were easier to realize when I reminded myself that pork is slaughtered pigs. That beef is slaughtered cows. That chicken is slaughtered chickens. That grocery eggs come from hens housed in industry conditions, not back yards.

Without my dad’s cholesterol, I would probably still perceive meat and living stock as unrelated forms of matter.

Enter the Mallards

Timing is everything, and my various perspectives and journeys are not random. If you are still reading, you might be starting to see a signal. Or not.

What looks like signal to me likely looks like noise to others.

Perhaps in a later post I’ll explain how a literature search through the history of prion testing catalyzed an ongoing reaction between a brood of suburban ducklings, a fetish-level case of nostalgia, a dysfunctional family history, and a stubborn set of lipid genes, resulting in this multi-part Mallard post.

For the present, I’m a recovering carnivore lured to herbivory by a longing to live past 52. I grew up in a rural environment where the animal protein on our table came from our own yard, pasture, and woods. And I’ve known what it is to be hungry.

These perspectives matter, though it’s not entirely up to me to decide how they matter.

In the next episode…

Mallard hunting is big business.

1. Were she still alive, Mother would never consent to publication of this photo. The awkward pose, the awkward pants, the cluttered background. But I was always one of her greedy chicks, always scolded and shooed with her free hand. Wherever she is, she’ll understand. She’ll complain, but she’ll understand. (Click here to return to your regularly scheduled photo caption.)

2. While I’m perfectly awful at recognizing genetic and cultural heritages based on peoples’ features and clothes, I recognize that this distant cousin doesn’t look or dress like my grandmother’s family. I would love to know more about her. (Click here to return to your regularly scheduled photo caption.)

3. My parents believed weasels were the chickens’ craftiest predators, blaming almost all egg, chick, and hen losses on an invisible and trackless family of mustelid carnivores, traceable only by scent. Years later, I realized that the scent I was taught to identify as “weasel” covered everything from the musk of a water snake to fox scat to mouse urine. (Click here to return to your regularly scheduled paragraph.)