‘When you have killed all your own birds, Mr. Bingley,’ said her mother, ‘I beg you will come here, and shoot as many as you please on Mr. Bennet’s manor. I am sure he will be vastly happy to oblige you, and will save all the best of the covies for you.’ –from Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Content Warning

This multi-part blog post contains references to hunting, agriculture, and research practices of killing birds. This particular installment references various methods and means of Mallard hunting, past and present. If you decide not to read on, I respect and admire your choice.

Limiting (and limited) expectations

It was easy to position my own context for these posts (see Part IV). But all of my (deleted) attempts to contextualize Mallards in pre-1800s North America have been as flawed as my knowledge.

It’s a given that there are records outside of the Mallard archive, outside of the Mallard mine, that explain how and why North America’s waterfowl maintained flagrant abundance within and around the continent’s early nations. But I don’t have a discourse for these records.

In the end, after all of my reading, I am not equipped to know North America’s pre-colonial Mallards, much less describe them. They are, for me, a personal singularity. An infinite intangible that disturbs my erratic journey.

In other words, I’m only telling one facet of the Mallard story: the part written by and for Europe’s descendants.

Caveat lector.

In medias res

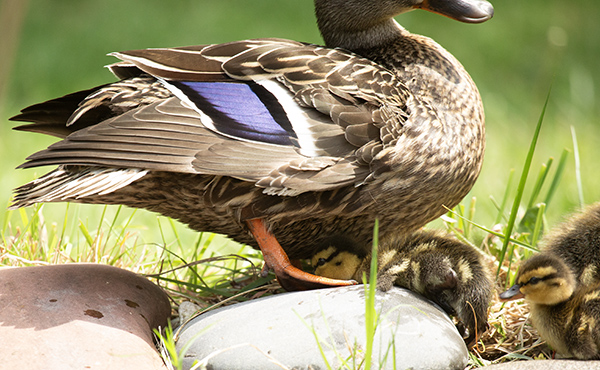

When I last left the Mallards, in the opening decades of the 1900s, their populations were collapsing. For the moment, I’m leaving them suspended in free-fall.

This post circles back to the 1800s. Back to an era of unchecked habitat destruction and overhunting. Back to the transition years, when state lawmakers claimed title over wildlife and began to legislatively dismantle game markets.

“Wetland utilization in North America provides a classic case of conflict in resource management. The disadvantages of marshes and ponds for the individual farmer encourage their drainage and conversion to cropland. At the same time, these wetlands provide vital habitat for migratory waterfowl, a principle wildlife resource…” (Pospahala, Anderson, & Henney, 1974, pp. 5–6).

“We, who cannot live without wild ducks, must first of all acknowledge two facts: 1. We are the minority; 2. The majority regards any land which is too wet to plow, but unsuitable for swimming or water boating, as useless” (Anderson, 1953, p. 122).

These were never the King’s ducks

After fleeing systems in which wildlife belonged to the aristocracy, the English and French colonists in North America drafted new rules. In the colonies, wildlife would belong to the citizens. To the People. (Not, however, to the People who already lived in North America. Only to those who staked their various flags along eastern coastlines and cascaded westward.1)

“The explorations of these settlers were driven by the incredible wealth of North America’s renewable natural resources—and by an unfettered opportunity to exploit it” (Organ, Mahoney, & Geist, 2010, p. 23).

Who killed (kills) the People’s birds?

During the glut years of the 1800s, US hunters took to the field in three different pursuits: subsistence hunting, sport hunting, and market hunting.

As subsistence hunters took (take) only what they need for survival, their impact on bird populations was (and still is) minimal. But sport hunters, in the 1800s, tended to binge. Each adventure piled up the carcasses:

“The geese were flying all day, thousands upon thousands of them. We killed 163 that day. We had a farm wagon with extra side boards for carrying eighty bushels of wheat. Our kill nearly filled that wagon box. I know that night when we drove back to Dawson, which I think was eight miles distant, we were cold and wet and we all stuck our legs down in the geese and the warmth of their bodies kept us comfortable” (Mershon, 1923, pp. 117–118).

After each binge, sport hunters returned to their families and their varied professions.

Unless the binge was their profession.

The Meat and Feathers Market

Between 1820 and 1860, America’s cities blossomed from a thin seeding of only 5% of the population to a significant 20% demographic. “Markets for wildlife arose to feed these urban masses and to festoon a new class of wealthy elites with feathers and fur” (Organ, Mahoney, & Geist, 2010, p. 23).

Market hunters earned a living harvesting the wildlife that lived in unclaimed (or claimed and unsupervised) wild places. The siren song of profit penetrated every field, marsh, and wooded acre, tempting hunters to abandon the traditional and self-imposed restraints that defined hunting as a sport.

“A momentary question goes through your mind. ‘Shall I give them the first barrel on the water?’ It is dismissed almost as soon, for early I have been taught it is not the way of the sportsman. Give the birds a chance is the rule. Yet I can not help hoping they will be well bunched and I can get more than one with the first barrel and hope for another with my second. Well, sometimes it works one way and sometimes another. Either way it’s the life worth living” (Mershon, 1923, p. 76).

Giving the birds a chance, for the market hunter, was a profit gamble.

It was highly likely that a hunter the next county over would happily shoot all the birds on all the waters, rules be damned.

The market wanted meat and feathers, so meat and feathers the market would have.

Any hunter willing to renounce the title of “sportsman” could cash in.

What would you have done?

Endless demand v. limited supply

Around cities and towns, market hunters drained the wildlife from marshes and woodlands and fields. And as nearby wildlife dwindled, sportsmen were forced further afield for their binges.

“Conflict soon arose between market hunters, who gained fortune on dead wildlife, and the new breed of hunters who placed value on live wildlife and the sporting pursuit of it” (Organ, Mahoney, & Geist, 2010, p. 24).

By the late 1800s, some of the birds had been hunted to extinction.

“The first bird I ever killed on the wing was a wild pigeon. They frequented the Saginaw valley in thousands from early spring until after the harvest. I had been taken with my uncle and father pigeon shooting many times to pick up birds. It was no trick for them to get seventy-five or a hundred birds before breakfast, and soon after I was given my 16-gauge double barrel gun I was taken out to shoot pigeons. The flocks were dense, as I now recall, so it was not a difficult feat to bring one down, and at the very first discharge a pigeon from my shot came fluttering to the ground. I grabbed it and admired it and was satisfied for that morning to have it my entire bag, and proudly took it home to show my mother. It was not long before I was going pigeon shooting regularly every morning, for the flight began at daylight and was generally over by seven o’clock. Then I would get my breakfast and be off to school. My pigeon shooting continued every spring until about 1880, when it was gone forever” (Mershon, 1923, p. 3).

“No ordinary destruction”

In the sport v. market skirmishes, sport hunters always had the upper hand. Reputation and tradition amplified their voices.

“Furthermore I will prove by sundry reasons in this little prologue, that the life of no man that useth gentle game and disport be less displeasable unto God than the life of a perfect and skillful hunter, or from which more good cometh. …he shall go and drink and lie in his bed in fair fresh clothes, and shall sleep well and steadfastly all the night without any evil thought of any sins, wherefore I say that hunters go into Paradise when they die, and live in this world more joyfully than any other men” (Edward, Second Duke of York, 1406–1413/1909, pp. 4, 11).

“It is stated that in their migrations northward, the waterfowl often reach the lake in the spring, while it is still covered with ice, and that while huddled in great numbers in the mouths of streams and other open places, they are slaughtered indiscriminately, and that while too poor and unfit for eating. It is also represented that they are killed and wounded in great numbers by the swivel or punt gun, which is a small cannon fixed to a boat, and that by these practices they are driven from their usual feeding grounds and places of resort. It is the well known habit of waterfowl to follow the same line and stop at the same points in their migrations, and such a serious disturbance at this great half-way station, may eventually result in their seeking other quarters. To prevent this it is asked that the killing of waterfowl in the spring be prohibited altogether in certain counties, and that the use of the punt gun be absolutely forbidden. The petitions upon this subject have been so numerous, and the petitioners so respectable, that there evidently must exist good cause for complaint, and their request should be granted. The use of the punt gun along the sea board has been made illegal for like reason, and if it is necessary there, it is still more so here” (Collins, 1860, p. 388).

“The ‘game hog’ is an animal on two legs that is disappearing. May he soon become extinct! The ‘game hog’ formerly had himself photographed surrounded by the fruits of a day’s ‘sport,’ and regarded the photograph as imperfect unless he had a hundred dead ducks, grouse, or geese around him. To-day a true sportsman would be ashamed to be pictured in connection with a larger number of fowls than a decent share for an American gunner, having due regard to the preservation of game for the future” (Lacey, 1900, pp. 4871–4872).

Haunted by pigeons

A single piece of market-favorable legislation murmurs from the archival cacophony: an 1848 Massachusetts statute that prohibited anyone from frightening passenger pigeons out of netting-beds, under threat of a $10 fine and compensation for damages (General Court of Massachusetts, 1848, p. 650).

It should be no surprise that this particular law is audible to search engines. After all, passenger pigeon extinction is a holotype cautionary tale that should linger.

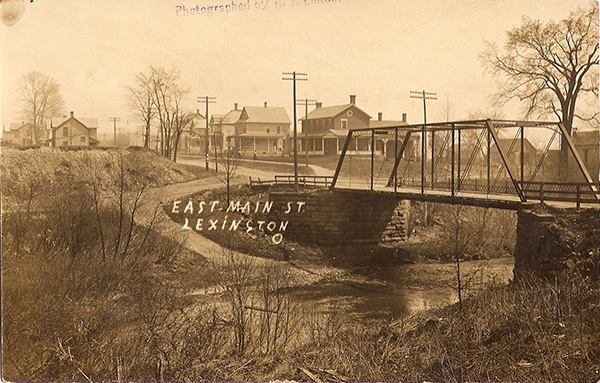

Ohio bids farewell to their big game, but assumes the pigeons will never die

In 1857, as the Ohio legislature sought to revise their “Act to Prevent the killing of Birds and other Game” (Ohio General Assembly, 1857, pp. 107–108), legislators requested assistance from the state’s Board of Agriculture.

The resulting work, published as a select committee report in 1860, wrote off Ohio’s big game as a lost cause: “Ohio has no waste land. It is all useful for agricultural purposes—if not for tillage, at least for pasturage. It has no sterile wastes, marshes, or mountain ranges where the larger game can find permanent security. The deer, the bear, the wolf, and such like animals will soon be gone, and laws that relate to them a dead letter” (Collins, p. 382).

Wild turkeys, prairie hens, and pheasants were in the same sunken boat. Excepting a few isolated flocks in isolated localities, no protections could save them. Even so, sportsmen wanted the legislature to regulate hunting, so hunting should be regulated. Ohio’s lingering populations of deer, turkey, prairie hens, and pheasants should be granted undisturbed breeding seasons (Collins, 1860, p. 384).

Seasonal protections were recommended for game birds that could adapt to progress—quail, meadow-larks2, kill-deer, doves, flickers, woodcock, and wood ducks (Collins, 1860, pp. 385-387)—as well as for waterfowl around Sandusky Bay (Collins, 1860, p. 389).

The multitudes of warblers, finches, and flycatchers were safe without protection. At least, being small, shy, and drab, they were safe enough. The food-and-feathers market didn’t covet such birds. Besides, providing bird-by-bird protections would require parsing dozens of common and scientific names (Collins, 1860, pp. 383-384).

Woodpeckers, blue jays, and blackbirds, the kind of birds that damaged agriculture when they ate crops but protected agriculture when they ate insects, could be left to the chances and whims of circumstance (Collins, 1860, p. 384).

The report singled out two game species as immune from overhunting (in Ohio) and in need of no protection: the snipe and the passenger pigeon.

Snipe were mere passers-through, fleeting visitors so well-camouflaged and difficult to flush from wet spring landscapes that only “practiced” sportsmen could hope for success (Collins, 1860, p. 387). During brief April sojourns, snipe were “good sport and a choice morsel for the table”, but “yearly numbers cannot be materially lessened by the gun” (Collins, 1860, p. 387).

And passenger pigeons?

“The passenger pigeon needs no protection. Wonderfully prolific, having the vast forests of the North as its breeding grounds, traveling hundreds of miles in search of food, it is here to-day and elsewhere to-morrow, and no ordinary destruction can lessen them, or be missed from the myriads that are yearly produced” (Collins, 1860, p. 387).

Forty years later, passenger pigeons were extinct in Ohio3 and functionally extinct everywhere else. It was, indeed, no ordinary destruction.

“Property of the State”

“Section I. That all the game and fish, except fish in private ponds, found in the limits of this State, be and the same is hereby declared to be the property of the State, and the hunting, killing, and catching of same is declared to be a privilege” (Arkansas General Assembly, 1889, p. 173).

“Section 4650, Wisconsin statutes of 1898 is hereby amended to read as follows: The ownership of and the title to all fish and game in the State of Wisconsin is hereby declared to be in the state, and no fish or game shall be caught, taken or killed in any manner or at any time, or had in possession except the person so catching, taking, killing, or having in possession shall consent that the title to said fish and game shall be and remain in the State of Wisconsin for the purpose of regulating and controlling the use and disposition of the same after such catching, taking or killing. The catching, taking, killing or having in possession of fish or game at any time, or in any manner, or by any person, shall be deemed a consent of said person that the title of the state shall be and remain in the state for said purpose of regulating the use and disposition of the same, and said possession shall be consent to such title in the state whether said fish or game were taken within or without this state” (Wisconsin General Assembly, 1899, pp. 576–577).

Such legislative grabs by Arkansas and Wisconsin, asserted during the closing years of the 1800s, didn’t materialize out of thin air.

State legislatures had been controlling the game within their borders since the 1820s, and courts had upheld a variety of statutes.

Let the alewives migrate

One of the earliest challenges to game laws came in Maine, after members of a town’s fish committee destroyed a dam on private property. On May 3, 1839, the fish committee took action on behalf of alewives, a type of herring.

Charles Peables had maintained a dam on his portion of Alewive Brook, in Cape Elizabeth, for some 12 previous years, diverting the water to power his mill. In May of 1839, local Fish Committee members Hannaford and Davis demanded that Peables open his dam and let the alewives pass.

When Peables declined, the Fish Committee disabled the dam in question. Litigation followed, and the Supreme Judicial Court of Maine eventually ruled for Peables, citing a technicality: Hannaford and Davis had acted early.

As the statute required the brook to be open May 5–June 5, Peables should have been able to run his mill straight up to the stroke of midnight on May 5. As long as the alewives could migrate upstream on May 6, Peables was not in violation of the statute (Peables v. Hannaford, 1841, 106).

Had Hannaford and Davis waited until May 6, they could have destroyed the dam at their leisure, and Peables could not have stopped them.

Peables v. Hannaford set a precedent, at state levels, for the states’ authority (embodied in local officers) to regulate game on private property.

“We see nothing unconstitutional in the Act”

On July 8, 1874, David S. Randolph served two dressed and cooked prairie chickens to diners in his St. Louis restaurant. According to a Missouri statute, these were the wrong birds in the wrong season.

Even though Randolph could prove that he had purchased the birds in Kansas, where July hunting was legal, he was cited and fined $9. Which would be about $250, today. Randolph appealed, but the Missouri Court of Appeals upheld the fines:

“We see nothing unconstitutional in the act. The game law would be nugatory if, during the prohibited season, game could be imported from the neighboring States. It would be impossible to show, in most instances, where the game was caught. The State of Missouri has as much right to preserve its game as it has to preserve the health of its citizens, and may prohibit the exhibition for sale, within the State, of provisions out of season, without any violation of the Constitution of the United States. So far as we know, this right has never been disputed, and its exercise by the absolute prohibition of the having in possession, or sale, of game within the State limits, during certain period of the year, is no more an illegal attempt to regulate commerce between the States than would be a city ordinance against selling oysters in July” (Missouri v. Randolph, 1876, p. 15).

Did you catch it?

In knotting up the import loophole, Missouri had stepped ever so softly on the interstate commerce boundary. And the appeals court didn’t mind.

‘…the congress shall have power to regulate commerce among the several states…’

When a somewhat related case landed before the Kansas judiciary, in 1877, the commerce question heated up.

On November 8, 1876, an agent for the carrier Adams Express Company received a package for transport—a shipment of four prairie chickens that had recently been killed. The agent, C. A. Saunders, delivered the birds to Chicago, and received a $10 fine (plus court costs) for his efforts.

Kansas had recently adopted the kind of boilerplate “no possession, no import, no export” law that was popular at the time. In Kansas, the wording had been adjusted to prohibit all import and export of game or birds, independent of season.

During open season in Kansas, in 1876, it was legal to possess prairie chickens that had been legally killed, as long as they had been killed within the state. During closed season, it was illegal to possess them at all. And it was illegal to import or export them, ever.

No matter the season, no one could move prairie chickens across the state lines.

Legislatively, this act seemed loophole-free. During open season, prairie chickens were fair game. Hunt them, eat them, sell them anywhere within the state of Kansas. All perfectly legal. But don’t ship them out of state. Don’t buy them out of state and bring them into Kansas. And during closed seasons, prairie chickens were entirely off-limits. Don’t kill them or have them anywhere in your possession.

The single exception written into this law involved shipments of prairie chickens that happened to pass through Kansas on their way to and from other states. Carriers handling such shipments were safe during their journey through the state.

The appellate judges for Saunders’s case glided straight past a series of technicalities regarding the title and wording of the act. They didn’t need to rule on those matters, because a larger issue took precedence:

“Section 8 of article 1 of the federal constitution provides among other things that, ‘the congress shall have power * * * [sic] to regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.’ Ever since the adoption of this provision, the judges of the supreme court of the United States seem to have been groping their way cautiously, but darkly, in endeavoring to ascertain its exact meaning, and the full scope of its operation. They have many times construed it, but as yet have hardly fixed its boundaries, or its limitations. They have no doubt generally construed it correctly, but some of their decisions with reference thereto seem to be conflicting and contradictory, and scarcely one of such decisions has been made without a dissenting opinion from one or more of the judges. We think however that amidst all their conflicts and wanderings they have finally settled, among other things, that no state can pass a law (whether congress has already acted upon the subject or not,) which will directly interfere with the free transportation, from one state to another, or through a state, of anything which is or may be a subject of inter-state commerce. …For instance, a law which prohibits the catching and killing of prairie chickens, may be valid, although it may indirectly prevent the transportation of such chickens from the state to any other state; but a law which allows prairie chickens to be caught and killed, and thereby to become the subject of traffic and commerce, and at the same time directly [emphasis in original] prohibits their transportation from the state to any other state, is unconstitutional and void” (Kansas v. Saunders, 1877, pp. 129–130).

This means game is commerce, right? And that the Kansas legislature had stepped a little too far over the interstate commerce boundary. Right?

It meant, at any rate, that Saunders didn’t have to pay his fine.

Preview of Part VII: More court cases, more decisions, and federal lawmakers patch the interstate commerce bug

The next post dives into game smuggling and game police. If you are starting to wonder if I’ve gotten game laws mixed up with prohibition laws, I haven’t, though there are certainly familiar elements.

Hold on to your feathered hats.

Also in the next installment, the courts decide that birds and game aren’t commerce, after all.

A note about previous previews: The schedule has changed, so the previews aren’t accurate

Even the most casual readers will have noted, by now, that this project is constantly expanding. Previews included in previous posts have been preempted and put off, as my reading has taken unexpected turns (I do love a good tangent).

My notes sprawl through four full composition books.

I will likely get to all of the topics introduced in previous previews, but not in order. I’ve given myself permission to keep exploring the Mallard mine, as long as my interest holds, and to keep chasing the tangents. My challenge, now, is to convince readers to keep exploring, as well.

If you’re still with me, Thank You!

Footnotes

1. This particular piece of the Mallard story, part of the pre-1800s history of North America’s colonization, is beyond both my tangent-tolerance (for these blog posts) and my philosophy/history horizon. Even so, an excerpt from a book assigned in a technical writing course resonates:

“Among the many arguments that Locke made in the Two Treatises is one that justifies appropriating lands from indigenous peoples where they are living in a state of nature. According to this argument, settlers who cultivate and improve the land—thereby rendering the ‘greatest conveniences’ from it—will have rights to the property:

“‘God gave the world to man in common; but since he gave it them for their benefit and the greatest conveniences of life they were capable to draw from it, it cannot be supposed he meant it should always remain common and uncultivated. He gave it to the use of the industrious and rational—and labour was to be his title to it (Second Treatise 137).’

“…British settlers under Locke’s rationale could claim property rights because they took resources from the land. These resources could be used to create a favorable balance of trade for England, where Board of Trade member Locke saw excessive imports as a source of unstable coinage practices” (Longo, 2000, pp. 51–52).

Mallards were one of the resources that colonists took and took and took. (Click here to return to your regularly scheduled paragraph.)

2. In 1885, while collecting in Canada, Robert Miller Christy wrote a love-note to Meadowlarks:

“I have often thought what a capital thing it would be to introduce the Meadow Lark in to England. So far as plumage and song are concerned, it would rank among our brightest-coloured and most admired songsters; while its hardy nature would allow of its remaining with us the whole year round, as indeed it often does in Ontario and other districts farther south than Manitoba. Perfectly harmless and accustomed to grassy countries, it would quickly become naturalised in our meadows, where it would find an abundance of insect-food, and would doubtless soon increase sufficiently in numbers to serve, if need be, as a game- and food-bird, as it largely does in the United States. No other songster that I ever heard equals this bird in the sweetness and mellowness of its notes” (p. 125). (Click here to return to your regularly scheduled paragraph.)

3. Ironically, Ohio’s deer rebounded. After being sentenced to local extinction, in 1860, deer found ways to survive in Ohio. And then conservation efforts across the 1900s helped deer to flourish. In the 2024–2025 hunting season, Ohio hunters bagged 238,137 white-tailed deer (Ohio Department of Natural Resources, 2025, para. 1). (Click here to return to your regularly scheduled paragraph.)

References

Anderson, J. M. (1953). Duck clubs furnish living space. In J. B. Trefethen (Ed.), Transactions of the eighteenth North American wildlife conference (pp. 122–129). Wildlife Management Institute. https://wildlifemanagement.institute/conference/transactions/1953

Arkansas General Assembly (1889). Acts and resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of Arkansas: passed at the session held at the capital, which began on Monday, January 13th, and adjourned on Wednesday, April 3rd, 1889. Press Printing Co. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433009076492&seq=193

Christy, R. M. (1885). Notes on the birds of Manitoba. In J.E. Harting (Ed.), The Zoologist, 3rd series, Vol. IX. No. 100 (pp. 121-133). John van Voorst, Paternoster Row. https://ia801303.us.archive.org/27/items/Zoologist85lond/zoologist85lond.pdf

Collins, W. O. (1860). Report of Senate Select Committee, upon Senate Bill No. 12, ‘For the protection of birds and game.’ In Fifteenth annual report of the Ohio State Board of Agriculture with an abstract of the proceedings of the county Agricultural Societies to the General Assembly of Ohio for the year 1860 (pp. 381-390). Richard Nevins, State Printer. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015038792258&seq=549

Edward, Second Duke of York (1909). The master of game: The oldest English book on hunting. (W. A. Baillie-Grohman & F. Baillie-Grohman, Eds.). Duffield and Company. https://archive.org/details/TheMasterOfGame/page/n7/mode/2up (Original work published 1406–1413).

General Court of Massachusetts (1848). Acts and resolves passed by the General Court of Massachusetts in the years 1846, 1847, 1848; Together with the rolls and messages. Dutton & Wentworth, Printers to the Commonwealth. https://archive.org/details/actsresolvespass184648mass/page/n5/mode/2up

Kansas v. Saunders, 19 Kan. 127 (1877). https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/7934084/state-v-saunders/pdf/

Lacey, J. (1900). Enlarging the powers of the Department of Agriculture. In Congressional Record, House of Representatives, Monday, April 30, 1900 (pp. 4858–4980). The Government Printing Office. https://www.congress.gov/bound-congressional-record/1900/04/30/33/house-section/article/4858–4980

Longo, B. (2000). Spurious coin: A history of science, management, and technical writing. State University of New York Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.18254358

Mershon, W. B. (1923). Recollections of My Fifty-years Hunting and Fishing. The Stratford Co., Boston. https://archive.org/details/recollectionsofm00mers_0

Missouri v. Randolph, 1 Mo. App. 15 (1876). https://www.plainsite.org/opinions/279xdv9rm/state-v-randolph/

Ohio Department of Natural Resources (February 4, 2025). Ohio’s final 2024–25 deer harvest report. Ohio Department of Natural Resources. https://ohiodnr.gov/discover-and-learn/safety-conservation/about-ODNR/news/ohios-final-2024-25-deer-harvest-report

Ohio General Assembly (1857). Acts of a general nature and local laws and joint resolutions passed by the Fifty-second General Assembly of the State of Ohio: At its second session begun and held in the city of Columbus, January 5, 1857 and in the fifty-fifth year of said state: Volume LIV. Richard Nevins, State Printer. https://books.google.com/books?id=S1lOAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA107#v=onepage&q&f=false

Organ, J. F., Mahoney, S. P., & Geist, V. (2010). Born in the hands of hunters: The North American model of wildlife conservation. The Wildlife Professional, 4(3), 22–27. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267749137_Born_in_the_hands_of_hunters_the_North_American_Model_of_Wildlife_Conservation

Peables v. Hannaford, 18 Me. 106 (1841). https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/5108727/peables-v-hannaford.pdf

Pospahala, R. S., Anderson, D. R., & Henney, C. J. (1974). Resource Publication 115: Population ecology of the Mallard II. Breeding habitat conditions, size of the breeding populations, and production indices. U. S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. https://nwrc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16473coll29/id/10213/rec/1

Wisconsin General Assembly (1899). The laws of Wisconsin, joint resolutions and memorials passed at the biennial session of the Legislature, 1899. Democratic Printing Co., State Printer. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89096040076&seq=7